Throughout the past decade and a half, New York City’s skyline-altering luxury building boom has produced no shortage of eye-catching, unmistakably contemporary landmarks. Some are twisting or gridded or stacked like Jenga blocks, others are sleek and supertall, and nearly all are clad in shimmering expanses of glass (see Hudson Yards). But there is another side to this story.

Amid the futuristic never-seen-that-before, stretching-into-the-clouds pyrotechnics, some of the city’s most prestigious new apartment high-rises are being designed by architects who unabashedly look to the past. While far from dyed-in-the-wool classicists, these architects are embracing and reinterpreting traditional design language, materials, and craftsmanship in pursuit of a stronger expression of character and a distinctive sense of home in urban buildings. Though it would be an overstatement to declare a full-blown movement, there’s no doubt these types of projects have momentum in New York and are beginning to gain traction, selectively, in other American cities. “Some people explicitly want to be in the newfangled thing, but a lot of others just feel more comfortable in a more traditional setting. People value character and a sense of place,” says Peter Pennoyer, one of the leading architects who has designed historically inspired, high-end residential buildings. That list also includes Steven Harris, William Sofield, Lucien Lagrange, and, most prominently, Robert A.M. Stern.

Indeed no one has been more influential or bankable in the luxury condo sphere than Stern, the former dean of Yale’s architecture school whose mantra, as he likes to say, is “Looking to the past to move forward.” Buildings by his firm, Robert A.M. Stern Architects (commonly shortened to RAMSA), have set the standard—and in real estate terms, become the model of success—for a new kind of urban classicism that draws heavily on the architectural history of his native New York, especially the apartment houses designed by J.E.R. Carpenter, Rosario Candela, and Emery Roth during the interwar period.

More From Veranda

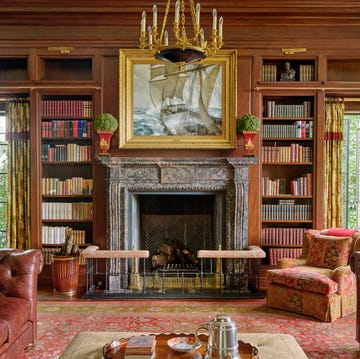

For a certain class of buyer, those venerable buildings, with their elegant limestone or limestone-and-brick façades informed by Italianate, Georgian, or Art Deco influences, have long been Manhattan’s ultimate prestige addresses. But while today’s buyers appreciate the generous ceiling heights and gracefully proportioned living spaces of the historic buildings’ original floor plans, they have no need for multiple servants’ rooms and expect larger baths and open, accessible kitchens where they can gather with family and casually entertain. Renovating these old apartments, even ones that have been updated over the years, can be a headache.

What Stern and others working in a similar vein bring is a level of aesthetic sophistication and luxury on par with the best classic apartment houses, only everything is new. Not to mention, there’s no co-op board to deal with. Stern has even adapted his approach to towers 60, 70, 80 stories high, affording supertall-caliber views.

The grandest of RAMSA’s New York projects, 220 Central Park South, completed a few years ago, is one of several ultraluxury residences that anchors so-called Billionaires’ Row. Composed of an 18-story, park-facing “villa” and an adjoining 950-foot-tall tower behind, 220 features façades of silvery Alabama limestone, punctuated by a rhythmic variety of windows, Juliet balconies, and setback terraces. The architecture’s understated classicism feels comfortingly familiar, almost from an earlier era, yet also fresh, modern even. And it has resonated with buyers.

Initial sales in the building approached $3 billion, including what has been reported as the most expensive home ever sold in the U.S., a 24,000-square-foot, four-floor spread acquired by hedge fund manager Ken Griffin for nearly $240 million. The address has been a magnet for high-profile figures from the worlds of entertainment and finance, as have many of Stern’s buildings since his watershed 15 Central Park West opened in 2008, establishing stylistic and material signatures RAMSA has continued to refine and expand upon.

“We cut a new direction, established a return to a new set of precedents, the 1910s to 1930s residential buildings, mostly on Manhattan Island, which were among the glories of that period of architecture in the United States,” says Stern. “The intelligence of the New York apartment house as it evolved was thrown out the window to a shocking extent after the Second World War. Now we’re bringing it back, and there is a real audience for that kind of approach.”

Rising Expectations

In the postwar decades even modern high-rises billed as luxury—whether white-brick, concrete, or glass-and-steel—too often fell into cookie-cutter monotony and plainness. Apartments tended to be standard built, one stacked on top of another with little variation, linked by long internal corridors that took up space and undermined any sense of homey intimacy. Pennoyer, whose firm has designed a couple of Upper East Side buildings and is working on a third, sees a shift. “There’s a rising expectation of what an apartment should be,” he says. “I don’t think people will any longer accept the low ceiling heights, cramped dimensions, and lack of detail that we saw in the ’70s, ’80s, and even the ’90s.”

Pennoyer is speaking, of course, about the upper echelons of the real estate market and the kind of buyers he was catering to with his 151 East 78th Street, a 17-story limestone-and-brick building rich with neoclassical details, and the just-completed Benson, an 18-story high-rise at 1045 Madison Avenue with its Art Deco–inflected façade of limestone and elegant ironwork that evokes prewar Paris and New York in equal measure. When it comes to the interiors of Pennoyer’s buildings—as with most of Stern’s—the residences are a thoughtfully calibrated balance of classic and contemporary. “You’re trying to bring various influences together and not just say, I’m going to try to replicate a prewar apartment,” Pennoyer explains. “You’re making something that’s absolutely contemporary but has those proportions and space and openness that we all prefer now.”

Intentional Idiosyncrasies

Some developers, no doubt aiming to give their building another selling point, opt to bring in a marquee designer to put his or her creative stamp on the interior spaces. Kelly Behun worked on the interiors of Stern’s 1228 Madison Avenue, for example, and Lauren Rottet is doing 200 East 83rd Street. At The Benson, Achille Salvagni was enlisted to amp up the lobby’s modern glamour, explains Elizabeth Graziolo, who left her position as a partner in Pennoyer’s firm in 2020 to launch her own practice, Yellow House Architects, though she continued to see The Benson through to completion.

The Haitian-born architect is in the early stages of designing her firm’s first Upper East Side residential building, while adding to her portfolio of historic renovations, including apartments in a pair of early-20th-century Financial District landmarks: The Woolworth Tower and One Wall Street. “In these iconic buildings, people feel like they are living a lifestyle of glamorous New York at its height,” says Graziolo, noting that conjuring a sense of romance and nostalgia is precisely what many new buildings aim to do. Experience with renovations at distinguished old New York addresses is one of the reasons Harris says architects like him have been tapped by developers to design apartment buildings in a similar spirit. “Also we work for a lot of the types of clients who are their potential buyers, so we have a sense of how they actually live and use spaces,” says Harris. Presently he is finishing a 20-story high-rise at 109 East 79th Street that’s clad in fluted limestone, pale Roman brick, and panels of exquisitely patterned Pietra di Torre stone that surround the double-height entrance featuring an abstract glass mural by Mig Perkins. The design was influenced, in part, by Harris’s love for the Villa Necchi Campiglio and the “kind of stripped classicism of 1930s Milan architecture,” he says, “what you’d call somewhere between neoclassical and Art Deco.”

Harris emphasizes that, as with the great prewar apartment houses, the design was dictated by the floor plans. “There are quite a few different apartment configurations that interlock almost like a Chinese puzzle,” he says. That complexity is reflected in the building’s varied fenestration and massing, which achieves a kind of balanced asymmetry, a characteristic common to the work of Stern, Pennoyer, and others that adds character to the silhouette and an appealing sense of idiosyncrasy. It can be seen in Sofield’s latest New York residential development project as well, the 30-story Beckford Tower and 19-story Beckford House, a pair of complementary buildings that stand a block apart on Second Avenue, at 80th and 81st streets.

“One of the things I love about old apartment buildings is how people over the years have screwed them up,” says Sofield, a self-described modernist by temperament and historicist by training. “Some rich person said, ‘Damn it, I want a bigger window,’ and they put in a bigger window—creating all these what for an architect would be considered mistakes. In both buildings, I kind of built in intentional idiosyncrasies, which I think makes them feel more authentic.”

The façades of both the house and the tower mix gray brick and limestone with buff brownstone, all hand laid in subtly asymmetrical patterns with varying color and texture, while window styles and dimensions shift with an unpredictable elegance. For Sofield, who is well-known for designing boutiques for luxury brands like Tom Ford, Gucci, and Bottega Veneta, distinctiveness and craftsmanship and channeling “emotional experiences” are paramount. He believes any revival of classically informed architecture is foremost a response to “the erosion of the character of neighborhoods,” resulting, in part, from “developers who saw an opportunity to throw something up quickly and with very little thought to craft.”

Gracious Living

Ultimately the discussion around architects looking to the past has everything to do with a renewed emphasis on quality, refinement, and thoughtfulness, as well as creating a connection to history and place. “Architecture is really emotional—we want people to react emotionally to what we do,” says Lagrange, who is based in Chicago. He recounts the story of a woman who approached him at a party to tell him she makes a point each morning of walking by his building 65 East Goethe, featuring a mansard roof and other Parisian-inspired neoclassical details. “It’s amazing,” he says. “Just walking by the building makes her feel good because of the detail, the ironwork, the doors, the finishes.”

Gracious Living

Lagrange’s current projects include an 18-story high-rise in Dallas called One Turtle Creek and a 34-story limestone-and-granite tower in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood that will recall, he says, the preeminent Art Deco–era apartment buildings on Astor Street. Having worked on plenty of glass buildings over the years, Lagrange notes that buildings with masonry walls and punched windows can provide a greater sense of domesticity. “When you go home, you want to be sheltered, in a cocoon almost,” he says. “In a glass tower, it can be a little scary or uncomfortable at the edge and you lose privacy. To me I want a wall, to contain the room and to have artwork and lighting.” It’s a sentiment echoed by other architects, including Harris, who says he has seen among his clients “a desire that an apartment be, if not refuge, at least an escape in some way.” Peter Lyden, president of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, sees a COVID-19 connection. “I think the pandemic has pushed some people into wanting to live like where their grandparents did. I know that sounds kind of funny, but they want familiar surroundings, private and really cozy rooms. It’s going back to this beautiful, gracious kind of living.”

Could the pendulum of taste in the urban real estate market be swinging toward more traditionally inspired architecture, at least at the top end? It’s interesting to note the classical design elements in a number of high-profile new apartment buildings that no one is going to mistake as anything but contemporary. Take SHoP Architects’ 1,428-foot, dramatically tapering 111 West 57th Street—heralded as the world’s skinniest skyscraper—which rises out of historic Steinway Hall with two of its four sides clad in alternating bands of undulating cream-colored terra-cotta tiles and graceful bronze scrollwork, nodding to an earlier era of New York architecture.

Some 20 blocks away, in the NoMad neighborhood, CetraRuddy’s 45-story Rose Hill tower has a glass façade ornamented with chevron-patterned metal ribbons and a shaped crown that echoes Art Deco landmarks like Rockefeller Center. In the Financial District David Adjaye’s 66-story 130 William adopts as its primary motif one of classical architecture’s most fundamental forms, featuring arched windows in gridded rows across its walls of dark textured concrete. And in Boston, Höweler + Yoon designed the 20-story 212 Stuart Street with a façade of glass and fluted precast panels of varying sizes arranged in a rhythmic pattern of variation and repetition.

None of this is rote classicism, of course, though there are connecting threads in the references and design language. It’s really about the aspiration to create something of quality that is distinctive—not entirely new but worthy of standing alongside the historic precedents that serve as inspiration.

Featured in our September/October 2022 issue. Written by Stephen Wallis.