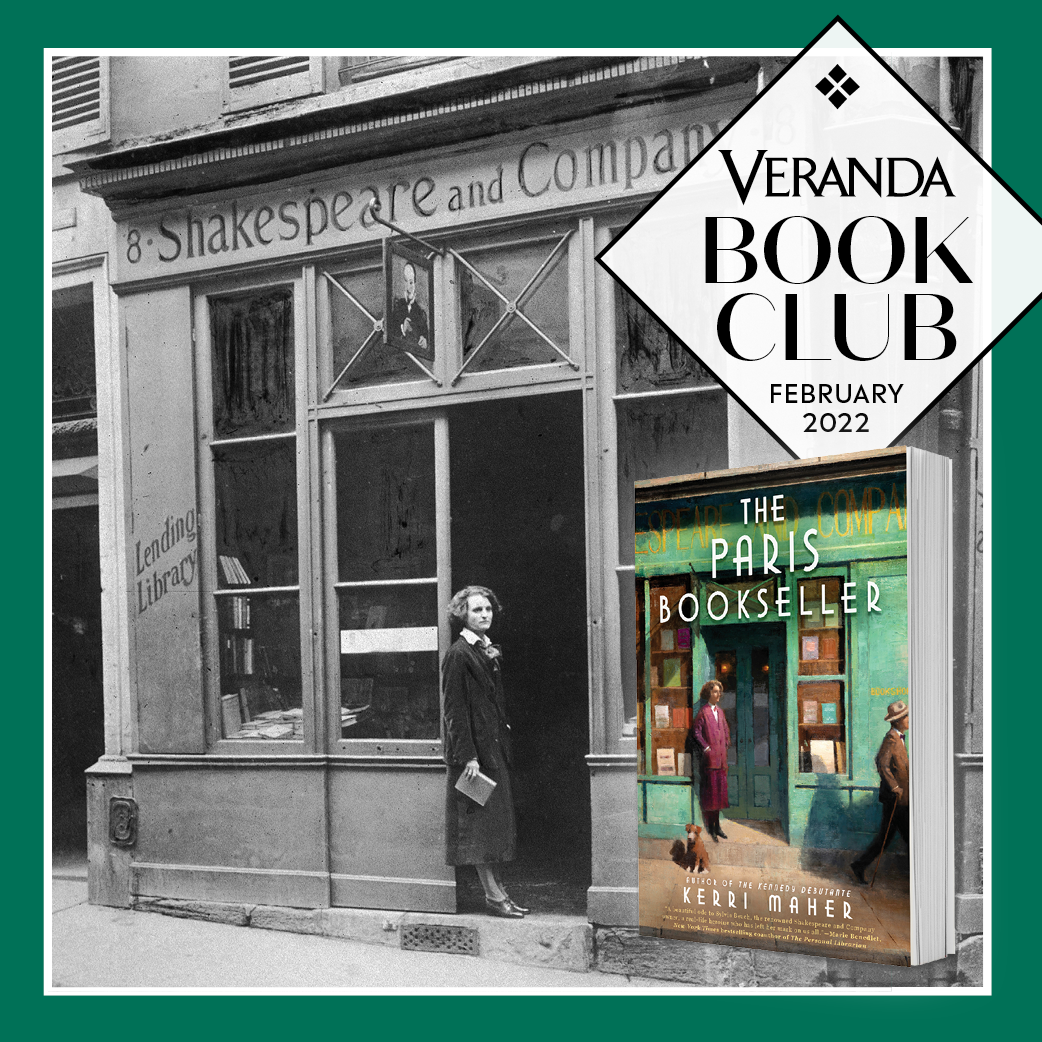

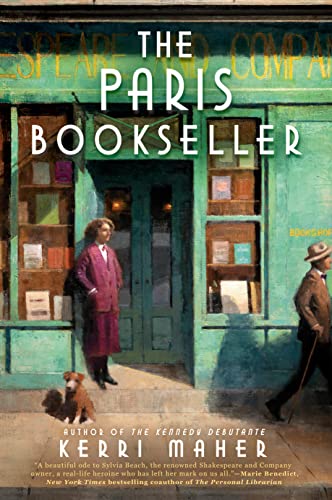

Welcome to the VERANDA Sip & Read Book Club! Each month, we dive into a book and offer exclusive conversations with the author, along with a perfectly matched cocktail. This month's pick is Kerri Maher's The Paris Bookseller, a compelling look at the real-life heroine behind one of Paris's most famous bookshops. Get caught up on our past book club selections here.

The year is 1919, and Sylvia Beach just opened the doors to her English-language bookshop on the artistic Left Bank of Paris. Inspired by French bookseller and her later lover Adrienne Monnier, the young American wanted to create an inviting place where she could share her passion for literature with like-minded people. Little did she know her little shop would become the cultural hub for writers, artists, and players of the Lost Generation.

Sylvia Beach and her shop, Shakespeare and Company, serve as the main characters of Kerri Maher's newest novel, The Paris Bookseller. The historical fiction sheds light on the landmark institution and Beach's role in helping creatives such as Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, and James Joyce become the literary greats they are known as today. Here, Maher reveals what it was like to give voice to such iconic figures and the lessons she learned about writing along the way.

More From Veranda

How did you discover who Sylvia Beach was? What about her life made you want to write a novel about Sylvia and Shakespeare & Company?

Kerri Maher: It’s amazing that it took me so long to write The Paris Bookseller because I’ve been carrying Sylvia’s story around inside me since I was 20 years old, which is when I read her memoir, a slim volume called Shakespeare and Company. I found an old paperback of it in a used book bin outside one of the many bookstores near UC Berkeley, where I was an English major obsessed with the 1920s. I was charmed by Sylvia’s recollections of her bookstore and lending library and the famous writers who frequented it and became lifelong friends; I was likewise fascinated by her remarkable publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses after it had been banned in an obscenity trial in 1921. She called herself a “booklegger,” because like the bootleggers of Prohibition she, too, smuggled and sold an illegal commodity in the U.S.

Fast forward 25 years, and after writing The Kennedy Debutante then The Girl in White Gloves; A Novel of Grace Kelly, I recalled Sylvia’s story and thought, "If anyone deserves the biographical fiction treatment, it’s her!"

I’m actually glad it took me so long to get to Sylvia’s story. I don’t think I could have written this novel when I was younger; I needed to have lived and loved and written all that I’d written to truly appreciate the ups and downs of Sylvia’s remarkable life. Also, I think that if I’d tried writing dialogue with Hemingway and Joyce in my first try at historical fiction, I might have given up! I’m just so grateful I had the opportunity to write her story more than two decades after discovering it the first time.

Can you talk about what the research process was like?

KM: I think the most challenging thing about this book was deciding when to stop researching and when to start writing; as I mention in my Author’s Note, I could have read about these characters for years and years—but then I am not sure I even would have been able to write a novel about them. I had to be selective. Noel Riley Fitch’s incredibly detailed and footnoted biography of Sylvia was extremely helpful in fleshing out those notable writers, especially because I needed to see them through Sylvia’s eyes. Fortunately, I had already read books by and about many other characters, like Ernest Hemingway, whose A Moveable Feast I devoured while I was myself a young person in Paris. I also read published volumes of Sylvia’s letters, including one of her correspondence with James Joyce. To better understand the world and people around Sylvia, as well as the obscenity trial of 1921, I also read a great deal of nonfiction, and I provide a select bibliography at the end of my book for readers interested in more information.

I am also very lucky to have been able to travel to Paris in the early stages of my research for this novel, in the summer of 2019. Retracing Sylvia’s steps up and down the rue de l’Odeon, exploring her neighborhood, eating exquisite French meals (with a good friend of mine, just like Sylvia would have done!), drinking Parisian coffee that I made in my tiny rented apartment kitchen, visiting the Rodin Museum and Sacre Coeur and the D’Orsay, and walking all over the city till my legs ached … all of that really helped me feel into what it would have been like to be Sylvia, an American who couldn’t believe her luck to call Paris home.

Even more amazing, I got to stay in a flat in the very building where Joyce and his family stayed in the summer of 1921 while he was writing Ulysses, an apartment he borrowed from the French poet Valery Larbaud, a very good friend of Sylvia’s. It was an address on the rue Cardinale Lemoine that Sylvia would have visited many times in the years she knew Larbaud, a place she actually mentions in her memoir. And just one block up the street was where Ernest and Hadley Hemingway first lived when they arrived in Paris.

How could I not be inspired by all of that?

Did you find it difficult to give voice to such iconic writers and Sylvia?

KH: James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound: these are mythical figures in literature, and I had to approach them with humility. It helped to learn in my research how amazingly human they were, however—just like I am, just like the many other excellent writers I am lucky enough to call friends.

I also constantly reminded myself that writers of historical fiction need to strike a difficult balance between truth and imagination in order to write a compelling narrative that doesn’t get bogged down in the research. We have to embrace a peculiar tension: we want to bring these people to life, to capture their essence, and get the major facts right; at the same time, however, we are keenly aware that we are writing fiction, which is always and necessarily an act of interpretation. My Joyce and Beach are not the same that another writer’s would be.

Inhabiting that paradox made writing this novel all the more rewarding and fun. I feel so privileged to have been able to write about these amazing people, my own literary mentors, to have them argue with each other, and champion and frustrate each other, and to show how essential Sylvia to them.

What inspired you center the novel on the working relationship between Sylvia Beach and James Joyce as they fight to publish Ulysses?

KH: When I’m writing a novel, I’m always looking for the most satisfying story arc, full of complicated and intimate relationships and personal growth. Sylvia has to go on quite a journey to get herself to the stage where she can publish Ulysses, then she undergoes many changes in the decade in which she publishes many editions before American publishers come to woo Joyce and his novel away from Paris. Also, I was fascinated by the way working together transformed Sylvia friendship with Joyce, and also her relationship with Adrienne and her store. All of those components led me to write about the period from 1917 – 1936, which centers the story of her publication of Ulysses.

Can you speak on the role literary magazines played during this time period and more specifically in your novel?

KH: Avant-garde literary magazines like The Little Review, The Dial, and The Egoist were the showcases of Modernism! In some ways, they were like the Instagram of the early 20th century, displaying the poetry, novel chapters, essays, and photographs that were at the absolute forefront of progressive thinking. Readers and collectors who were interested in what was new, and what was next, followed these journals, and the content within the pages sparked debate and inspired other writers and artists to push the boundaries of style and content further and further. Sometimes, they actually dared writers to do better, to do more. In 1916, Margaret Anderson published an entirely blank Little Review with a short editor’s letter basically saying to prospective artists, “Is that the best you’ve got? Send me better!” Shortly after, she began serializing Joyce’s Ulysses.

Many literary lovers, specifically of 20th-century works, may be familiar with the history of Shakespeare & Company. What was it like to give life to the renowned Shakespeare & Company while still honoring a place literary buffs hold dear to their heart?

KH: It was a little intimidating, I cannot lie! But since I had such a deep and life-long reverence for the store, and Paris, and the whole milieu of the 1920s, I was determined to write the kind of book I’d like to sink into as a reader. In fact, that’s often one of my tests of a scene: Would I want to read this? If not, it has to go.

As a young writer, I also worked in an independent bookstore and in the rare books department of a library, so I was able to bring an authentic and personal love of books and bookselling to my representation of Sylvia’s iconic store—the kind of personal love you can sense that Hemingway also felt when writing about Shakespeare and Company even years after the store closed.

The original Shakespeare & Company served as bookshop, a publishing house, and even a meeting place for writers. What is the lasting impact of Sylvia’s Shakespeare & Company in today’s literary world?

KH: Sylvia Beach was instrumental in changing the course of literature in the 20th century with her own amazing work of art, Shakespeare and Company, and by publishing Ulysses when no one else had the courage to do so. She was a woman who believed in her own convictions deeply enough to go after what she wanted in spite of her own fears, flouting the powerful lawyers, judges, and publishers who lacked the vision and fortitude she possessed.

Sylvia’s Shakespeare and Company lives on in all independent bookstores and libraries, for they matter today as much as they did 100 years ago. They are still meeting places of neighbors and artists, hotbeds of interesting ideas, and support networks for the act of reading itself. Local booksellers and librarians take pride in placing exactly the right book into a patron’s hand, changing their lives forever—just like Sylvia did in Shakespeare and Company.

Sarah DiMarco is the Assistant Editor at VERANDA, covering all things art, design, and travel, and she also manages social media for the brand.