In northern Italy, in the Brescia Province of Lombardy, lies a fountain of youth. The fresh winds blowing in off the Alps have something to do with it; the lake, too, the way it stretches down from the mountains like a shimmering green tail. Polished mahogany speedboats glint across the surface, skimming past bathers cooling off along the shore—a scene from The Talented Mr. Ripley were it not for the noticeable lack of Hollywood here. There’s little glitz, no remnant aristocracy. What the villages cradling Lake Iseo have are vineyards, lots and lots of them, and a young, well-heeled wine trail luring Champagne-tier oenophiles from all over Europe.

You won’t find many Americans, likely because Franciacorta—the sparkling, exceedingly clean wine that shares the region’s name—is a relative neophyte among its peers. For centuries gentlemen vintners used the glacier-born soil to produce simple whites and reds for their tables and to share with neighbors. It wasn’t until the late 1950s that one of them became restless: Hobbyist Guido Berlucchi enlisted friend Franco Ziliani to help him improve upon his still white wine. A burst of experiments and a bubbling of energy followed (yeast, rest, rotate, repeat), shaking the emerald foothills awake. The wines began to sparkle. The initial corking was 1961, late by European standards (Franciacorta’s cousin to the east, Prosecco, has been around since the mid-18th century; Champagne arrived about 100 years before that). But Franciacortans aren’t inclined to rush anything, least of all wine. For all their youthful energy, the 121 wineries in the DOCG appellation—the highest designation of quality for Italian wines—bear an old soul. Bundles are handpicked, the rain comes when it comes (no irrigation or pesticides permitted), and bottles sit in cellars, some lit by candles, until the bubbles arrive—a second fermentation that, unlike Prosecco or Champagne, can last anywhere from 18 months to five years. A minimum of three years pass from harvest to market.

“The idea is to capture the purest expression of the grapes,” explains Arianna Biagini of founding producer Berlucchi. The largest in the appellation, the pioneering Borgonato winery operates alongside the quietly regal Palazzo Lana, a 16th-century manor that belonged to Guido Berlucchi before his death in 2000. Liberty-style frescoes grace vaulted ceilings in the dining room, while a jeweled bullfighter uniform hangs in a herringbone-paneled library overlooking the company’s flagship vineyard. In the cellar below, Berlucchi and Ziliani’s first successful bottle remains, along with blast rings on the stone walls from their early pressurized experiments.

More From Veranda

What Ziliani in particular recognized was a virtuoso-like alchemy of earth and atmosphere in Franciacorta’s hills. They are sheltered from humidity, with a wealth of morainic, mineral-rich soil, making them ideal, Ziliani argued, for growing the varietals most suitable for sparkling wine (Pinot Blanc, Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir grapes).

Yet the region had been largely impoverished since the Middle Ages when communes of monks inhabited and worked the land (Franciacorta means “free from taxes,” a concession given by the government to the religious orders for their service). Today monasteries remain, as do charming medieval villages that rise from the lake like terra-cotta empires. Courtyard bistros in towns like Iseo, Sulzano, and Clusane stir to life in the afternoons, with locals and visitors lingering over plates of antipasti and just-corked bottles. As if testament to the wine’s high-tier brio, the restaurant scene is flourishing. Hostaria Uva Rara in the vineyard-rich village of Monticelli Brusati serves Brescian-style dumplings and rose cake from the arched dining room of a 15th-century farmhouse, while the Michelin-starred Dispensa Franciacorta doubles as a wine shop and tavern. Most intoxicating, perhaps, is the waterfront veranda at Hotel Araba Fenice restaurant, where ducks paddle beneath guests dining on smoked trout and sipping sparkling rosés, bruts, and satèns (the latter, a light-as-air white produced only in the appellation).

With only 20 percent of the bottles finding their way out of Italy (a fraction of which make it to the United States), Franciacorta is as much pilgrimage as playground. An open-door warmth radiates from the wineries, many of them small, family run, and stretching down the same hillsides as ancient castles luring visitors to their frescoed walls and rose gardens. Tours of cellars and vineyards are often given by owners whose grandparents tended the grapes before them. Among these wineries, Le Marchesine in Passirano, with two of the oldest Pinot Blanc vineyards in the appellation, and Al Rocol, perched on a steep hillside in the highest part of the village of Ome. Aromas of sage and olive trees drift onto a shaded patio as Al Rocol’s co-owner Francesca Vimercati Castellini, who runs the fourth-generation winery, restaurant, and 16-room inn with her brother Gianluigi, talks of her grandparents making wine to share with neighbors.

Behind her linen panels blow in the breeze, shading a cool sienna-hued porch attached to the winery. Just inside the entry, a couple of small boxes sit on the floor. Taped to the top of each are handwritten addresses, marked USA. Private clients, says Vimercati Castellini. Perhaps even day-trippers from Lake Como, who chased a quiet route east to explore a sparkling wunderkind.

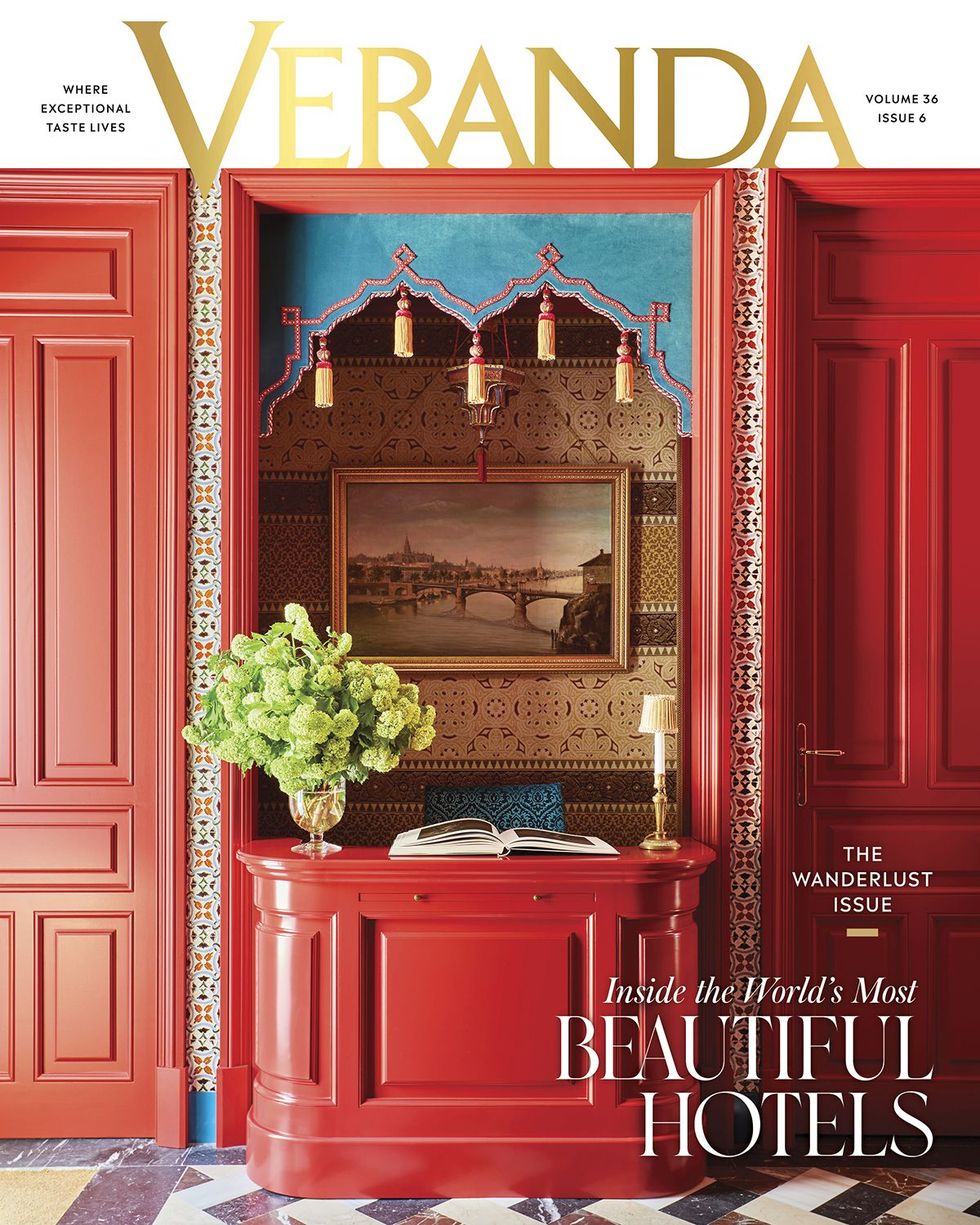

Featured in the November/December 2022 issue of VERANDA.