Recognizing a plant’s symbolic and ecological value as intrinsic to supporting life, from insects to birds and mammals, has become a cri de coeur in 21st-century garden design. And yet 101 years ago, a group of horticulturally minded society women in Virginia had exactly the same idea.

The founding mothers of the Garden Club of Virginia (GCV, now with 48 member clubs and 3,400 volunteers) dug in to restore historic gardens like those at Mount Vernon and Monticello, battle landscape despoilers like billboards (one member, Edith Sands, is legendary for wielding an ax to chop them down), and lobby for the establishment of national and state parks.

Perhaps most presciently, though, the founders spoke up for native plants. Realizing the native beauty in local species like dogwoods, which were losing ground to development, these skirted firebrands took their progressive message statewide. In 1928, the club sponsored an essay competition for children (with a five-dollar prize) on why it was important to protect native plants.

More From Veranda

Nearly a century later, the GCV—in addition to raising millions of dollars for good works from preservation to education—continues to spread the native-plant gospel. Some individual clubs have reached out to local city and town planners to promote the planting of native pollinators in home gardens and communities. “Resting on our laurels is not an option,” says GCV President Missy Buckingham.

That ideal is shared by the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach, which is waging its own velvet battle for the hearts, minds, and hedges of its citizens. “Plants are more than just wallpaper,” says Executive Director Amanda Skier, taking canny aim at the local addiction to ficus benjamina.

Deployed since the 1980s in privacy hedges, the species requires outsize watering and monthly pesticide spraying to keep the voracious whitefly at bay but kills off other insects that local birds need to thrive. (The Preservation Foundation has even created an “educational hedge” display with eight native shrub options to use instead.) It’s an existential obligation, she says, to help Palm Beach promote the indigenous flora and fauna of South Florida—an interpretation of preservation that leaps forward from bricks and mortar into environmental activism.

It’s not the first round for the foundation, which turned a small downtown plot into Pan’s Garden, a pesticide- and herbicide-free native jewel, in 1994. Now, though, they’re swinging for the hedges with an ambitious plan to remake the city’s 18-acre Phipps Ocean Park in a botanical language that restores its preexisting ecologies.

Leading the design is famed landscape architect and native planting guru Raymond Jungles. “I have the opportunity to bring back at least 100 species,” he says, adding that the project will exemplify the joy of garden design that embraces native plants. “You take a little kid into a garden that’s sterile, and you don’t see any sparkle in his eyes. You take him where there are butterflies and squirrels, you see that sense of wonder. I want to see more of that.”

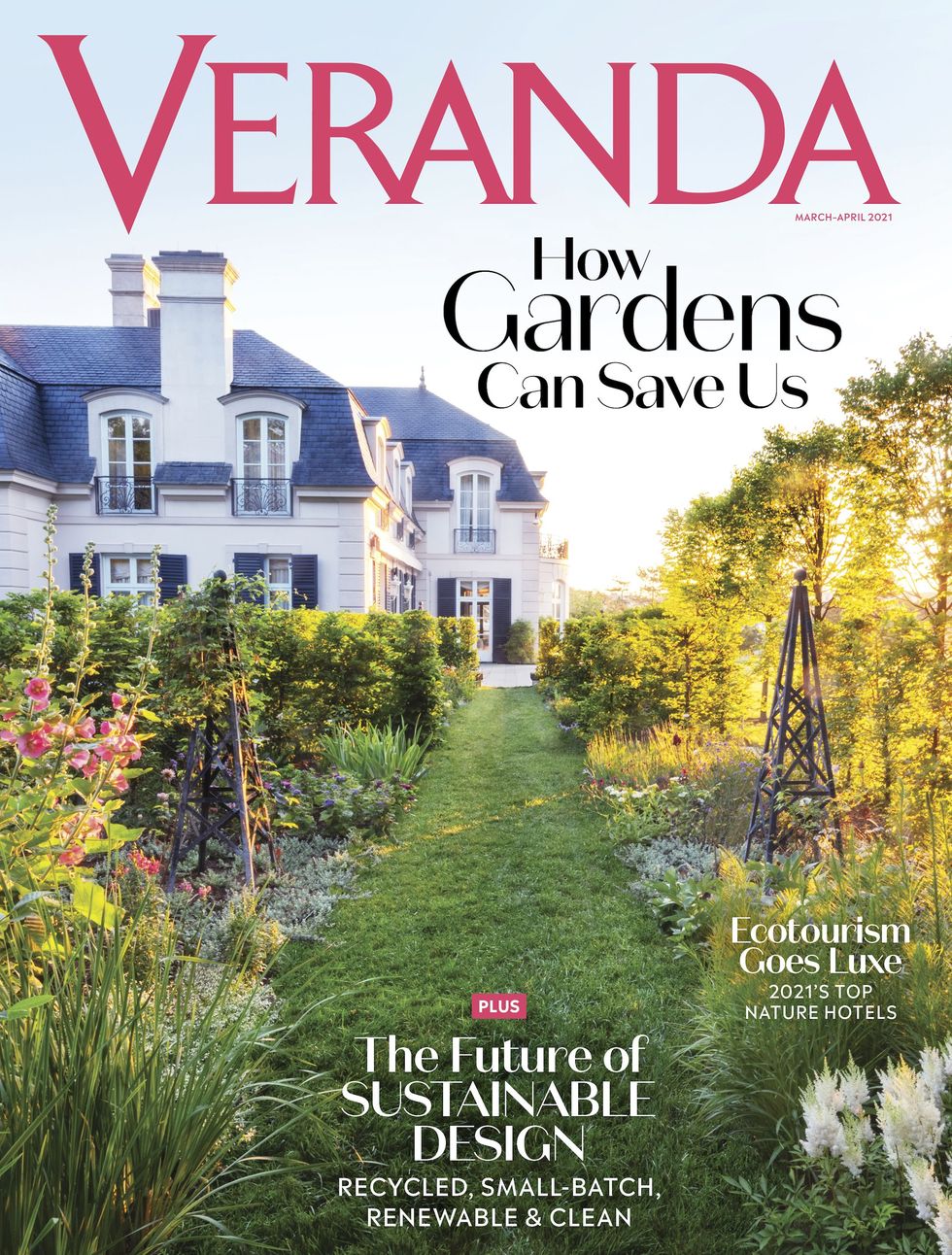

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2021 issue of VERANDA.